It’s Fall 1981, in a White Hall dorm room. Jim Madigan wakes up for his very first collegiate home game playing at the historic Matthews Arena. He’s a 19-year-old freshman with no idea of the career at Northeastern University that lies ahead of him.

Fast forward 44 years. Madigan, now 63, sits in his office on the second floor of the Cabot Center. If there was a street-facing window, he could overlook the fenced-in, empty plot of dirt now occupied by construction vehicles and hard hats where his freshman year dorm once stood. Just a few steps away, there is a boarded-up door that once housed the local establishment he worked at in the offseason.

Things have changed on Huntington Avenue.

The next big change to Northeastern is one that hits close to home for Madigan’s inner 19-year-old hockey player. However, at the same time, as athletic director, he has a key role on the team — spearheaded by Northeastern President Joseph Aoun — tasked to undergo the University’s next trademark development.

For Madigan, this next big change is a chance to create something “generational” for Northeastern University. In fact, the Matthews Arena project may stand as a monument for both Jim’s career and another signature of the innovation that Aoun has brought to the institution.

Madigan first stepped foot on the campus of Northeastern University in late September. He and his parents’ first stop after the drive from Toronto was the arch of Matthews Arena to drop off his hockey gear. It was the first step in fulfilling a childhood dream: playing college hockey in the United States.

“For me, it was always [the goal] to come down, go to school, play hockey, and further [my] education [in the United States],” Madigan explained. “It was alluring to be down in the States, but for me it was also ‘I’m going to Boston.’ I grew up in Montreal [and] Toronto, two major cities, [and] hockey was big [in] both those cities. Hockey was [also] big in Boston, so I was excited just to get here.”

At the time, he knew very little about Northeastern. He had been to Boston and other areas of Massachusetts to play hockey as a child, but short of a few former teammates playing at the school, it was new to him.

“I’d been to Boston before on some hockey exchanges or outside of the Boston area. I knew enough about Boston because of the sports,” Madigan said. “I grew up in the heyday of the Montreal [Canadians and Boston] Bruins rivalry in the early-to-mid ‘70s, and the Red Sox we all knew about. So, people were infatuated with Boston when I was coming down, because it was a major league sports town. [I] didn’t know much about Northeastern other than two kids who were on my junior team were here [as freshmen the year before me].”

Over the next four years, Madigan played in 119 games for the Huskies, registering 78 points (34 goals, 44 assists), and donned an ‘A’ on his sweater as an assistant captain during his senior season (1984-85).As a freshman, he was an integral part of the 1981-82 Northeastern squad that beat Bowling Green in March of 1982 to become the lone Huskies team to appear in a Frozen Four. He scored 32 points — 13 of which were goals — during the 35 games he played that season.

That year, and that game against the Falcons, where Northeastern scored the game-winning goal in overtime — a goal he, in fact, helped to set up — in front of a jam-packed Matthews crowd, has left a lasting memory on Madigan even 43 years later.

“Back then, the format was a two-game, total goal series,” Madigan said. “[The] first game [ended] 2-2. [The] second game was also 2-2 after regulation. Jerry York was the head coach for Bowling Green at the time. They had three All-Americans, including Hobey Baker award winner, George McPhee — he’s the president, now, of [the] Vegas [Golden Knights], Brian MacLellan — who was the [General Manager] of Washington, and a guy named Brian Hills — [a] longtime assistant coach at RIT. And they had a slew of other great players, but they had three All-Americans.

“And we beat them [on] the first shift in overtime. Our line started, and I helped set up the winning goal [in] the first minute of play,” he continued. “There was pandemonium on the ice. Kids came on the ice; we were all dancing. We [knew that] by winning, you’re going to the Frozen Four. … It was the first time any program at Northeastern [had gone] to a Frozen Four championship, whether it be the men or the women. So that memory, … that experience was just tremendous.”

Toward the end of his junior year at Northeastern, Madigan became increasingly drawn to the idea of pursuing a career in coaching hockey after college.

“Okay, maybe those opportunities of [playing] pro aren’t going to be there, but I want to be involved in the game,” he reminisced of his reasoning. “How can this maybe parlay into something bigger and better?”

Two years later, he leveraged Northeastern’s co-op program to kick-start his coaching career, joining the University of Vermont’s staff as an assistant coach in 1985. The eight months he spent as a co-op working on Vermont’s bench gave Madigan the necessary experience he would need when applying for future coaching jobs.

The following fall, he found himself back on the home-team bench at Matthews Arena. However, he was no longer in hockey gear, but in a suit as an assistant coach at Northeastern until 1993, when the NHL’s New York Islanders called.

For the next 18 years, Madigan worked in the Islanders’ and Pittsburgh Penguins’ scouting departments. Still, Northeastern always stayed in the fold. He continued to work at the university in various administration roles for both athletics and academics, all whilst scouting at the NHL level.

Following the 2011 hockey season, then Northeastern head coach Greg Cronin left the school for an NHL assistant coaching position. This left the Huskies’ bench vacant and created an opportunity for Madigan to get his first job as a head coach.

Due to his experience in hockey, coupled with his long-standing relationship with the university and its athletic department, when Madigan threw his hat in the ring for the head coach position, he knew he had a good chance to land it. But he also knew that he had not coached in a while and had never been a head coach. So when then-athletic director Peter Roby hired him, it was somewhat of a risk. Madigan credits Roby for taking that chance on him.

“I’ll always be indebted to [Roby] for providing me the opportunity to be the head coach,” Madigan said. “I hadn’t coached in 18 years. How many [expletive] people are going to hire someone who hasn’t coached in 18 years? Not many.

“He had [belief] in me, which I appreciated, to give me and afford me the opportunity,” he continued. “He knew I had passion for Northeastern. He knew I had passion for Northeastern hockey. But think about it. Would you hire a coach who hasn’t coached in 18 years and was never a head coach?”

Hey, it worked out for him, though.

“Yeah, [the] first couple years, maybe not, right?” Madigan admitted. “He was taking a lot of bullets, Luke. But, you know, he was someone that I learned a lot from in many different ways. Not just my hiring, but as he ran the department, I learned an awful lot from him.”

Freshly hired as head coach, Madigan’s next task was to assemble a staff that he knew would help him achieve success, and he knew the exact person to call: Jerry Keefe.

Keefe, like Madigan, has built a tremendous career centered around a passion for hockey. The Billerica native played four years for the Providence Friars before continuing to professional hockey at various levels both domestically and abroad.

After playing, the natural transition for Keefe was to coaching at the collegiate levels: an assistant coach for UMass Boston (2006-07), head coach of Westfield State (2007-09) — rebuilding that program from dormancy, and an assistant coach at Brown (2009-11), before eventually joining Madigan at Northeastern in 2011.

“[A] reason why I had so much respect for [Madigan] was we were always in the rink,” Keefe said. “We’d see each other all the time, and I think we both had a lot of respect for [each other’s] work ethics.

“I always enjoyed talking to Jim when I’d be at games,” he continued. “[We] talked about players and we talked about teams, and, at the end of day, we talked about hockey. So, that’s how our relationship kind of started. And then obviously, when he got the job, I believe I was the first phone call he made — which meant a lot to me — and kind of the rest is history from there.”

Over the 10 years they were together on the Huskies’ bench, Keefe and Madigan assembled quite the on-ice resume: eight-straight winning seasons (2013-21), a 174-132-39 overall record, the school’s first Beanpot Championship in 30 years (2018) — plus two more consecutive championships in the following years, two Hockey East titles, and three NCAA Tournament appearances.

They also developed numerous players into NHL-level talents, including the program’s first Hobey Baker award winner (Adam Gaudette) and two Mike Richter award-winning goaltenders (Cayden Primeau and Devon Levi).

“He was a tremendous coach,” said former Northeastern Athletic Director Jeff Konya of Madigan. “He is a great resource. He’s ‘Mr. Northeastern’ in a lot of ways. He did some great work in the development office, as well as what he did at Northeastern previously as an assistant hockey coach and [in] other positions…

“He’s got [a] great personality, super fiery, very competitive — [I] love that about him too,” Konya continued. “And he’s a very good leader. I thought that he commanded respect in the locker room and with the team, certainly amongst his colleagues as coaches and fellow administrators.”

Konya oversaw Northeastern’s athletic department from 2018 until 2021 while Madigan and Keefe continued to develop Northeastern’s hockey program into the established NCAA competitor that it is today.

But, in June of 2021, when Konya moved on from Northeastern to fill the athletic director position at San Jose State, it became apparent that Madigan was best fit to transition from ‘Coach Madigan’ to ‘Athletic Director Madigan’ at Northeastern.

“It did make sense, at least to me, that [Madigan] was hired in the athletic director role given all that context and history,” Konya said. “And, I think he’s done a very good job in the role.”

Even after Madigan had moved on from the rink, both Madigan and Keefe note how they built a lasting friendship behind the bench, even with a slightly different working relationship now from when they were both coaches.

“We’re really close friends, but the dynamic always shifts [and] changes,” Madigan explained. “I mean, we still have a good relationship, and I was his boss back then, as I am now, but it’s still a different dynamic. Our friendship remains the same, but the reporting structure is different.”

Keefe made a similar remark:

“It’s different now because we don’t see each other every day. And, we still talk an awful lot, but he obviously has a lot of things going on,” Keefe said. “I could pick up the phone [if] I needed any advice, just like when he was [coach]. I said it before: he was my boss for 10 years, when I was an associate coach, and now he’s my boss [still for] the last five years as the athletic director.

“So that hasn’t changed,” he continued. “[Coach Madigan is] still someone that I have the utmost respect for, someone that I lean on for advice, and someone that I take a lot of pride in working for because I know how much he cares about the hockey program here.”

With all that said, though, the June 17, 2021, promotion from coach to director was not particularly seamless. In fact, Madigan called the transition “baptism by fire.”

Exactly four days after he assumed the role, everything changed in the NCAA.

On June 21, 2021, the United States Supreme Court came to a unanimous (9-0) ruling on the case National Collegiate Athletic Association v. Alston (a.k.a. The Alston Lawsuit). The result affirmed the complaint that the NCAA’s restrictions on player compensation violated antitrust law.

From this judgment came the ability for collegiate players, at the Division I level, to be compensated for their Name, Image, and Likeness, now more commonly referred to as NIL, effective July 1, 2021 — two weeks after Madigan became athletic director.

“When I came into the athletic director’s role, there was a changing landscape overnight, in two weeks,” Madigan said. “It was like, … ‘We gotta come up with an NIL policy, right?’ It’s like, ‘How do I do this?’”

Leading up to the official announcement of NIL, there were talks about changes on the horizon, but for the most part, it came as a surprise for everybody.

“Some of it you could predict; some of you couldn’t predict, especially some of the specifics,” Konya said. “We certainly would have conversations about what the national scene was looking like and preparing for all that.”

In the years since the introduction of NIL broke open and fundamentally changed the way college sports operate, Madigan and Northeastern have taken various steps to introduce programs that allow the school the ability to allocate up to $20.5 million in revenue-sharing funding to compensate certain athletes at the university.

Importantly, Northeastern elected to opt in to the House Settlement. That decision, Madigan says, provides “flexibility” to the department to make decisions when it comes to allocating funds.

“We thought it was important at Northeastern,” Madigan explained regarding why Northeastern decided to opt in to the House Settlement. “Myself [included], but more importantly, the leadership of the university, from President Aoun to Ken Henderson, our chancellor, to give ourselves the flexibility. If we wanted to increase the number of scholarships in a certain program, we could do that, so we opted in.”

Still, the introduction of NIL, along with the explosion of the already semi-established Transfer Portal, created a new dynamic in college sports where schools are constantly competing monetarily to recruit and retain top-end talent.

“In today’s landscape, in order to be competitive, you need to retain your best student athletes,” Madigan admitted. “The best student athletes are being offered dollars every year to go to schools that resemble Northeastern academically and athletically, and they are free agents every year, the way this new system works. We want our student athletes, when they come in as freshmen, to graduate.

“We know we’re not going to be able to keep everyone, unfortunately,” he continued. “That’s just the landscape, but we want to make sure we can do our best in keeping as many of our student athletes as we can, and that’s what we’re going to try and do. And that means utilizing your revenue-sharing dollars to compensate not all of our players, but some of the players, and certainly the ones that are difference makers in their respective sport.”

In Madigan’s opinion, “the only constant in college athletics is change,” which he says creates “some challenging decisions that have to [be] made not just on Northeastern’s campus, but on many of the [college] campuses.”

“I think whether people like what’s going on in the NCAA or not is irrelevant,” Keefe said. “Those are the rules, you’ve got to play by them. And now, we’ve got to go do as much as we can to play within those rules, to be the best program we are. That’s always been how [Madigan] is. He’s always trying to find the extra whatever we can do to be as good as we can be, and I think that has not changed at all.”

As Madigan took over the athletic department in a period of transition and constant change in college athletics, he also understood that there was another challenge facing him — a historic venue that was potentially on its last legs.

In September of 2021, months after taking the job, Northeastern began conducting evaluations of the infrastructure of Matthews Arena and weighing possible plans to renovate or expand it.

Within a year, it became apparent that a renovation of Matthews wasn’t a possibility, and that meant Madigan would be a part of a team needed to spearhead a university-wide effort to fund and plan a replacement.

“President [Aoun] asked me when I took the job, … I remember he asked the question, ‘What do we need to do, Jim, to enhance athletics?’” Madigan said. “And I said, ‘Three things, Mr. President,’ and he looked at me, and I said, ‘Facilities, facilities, facilities.’”

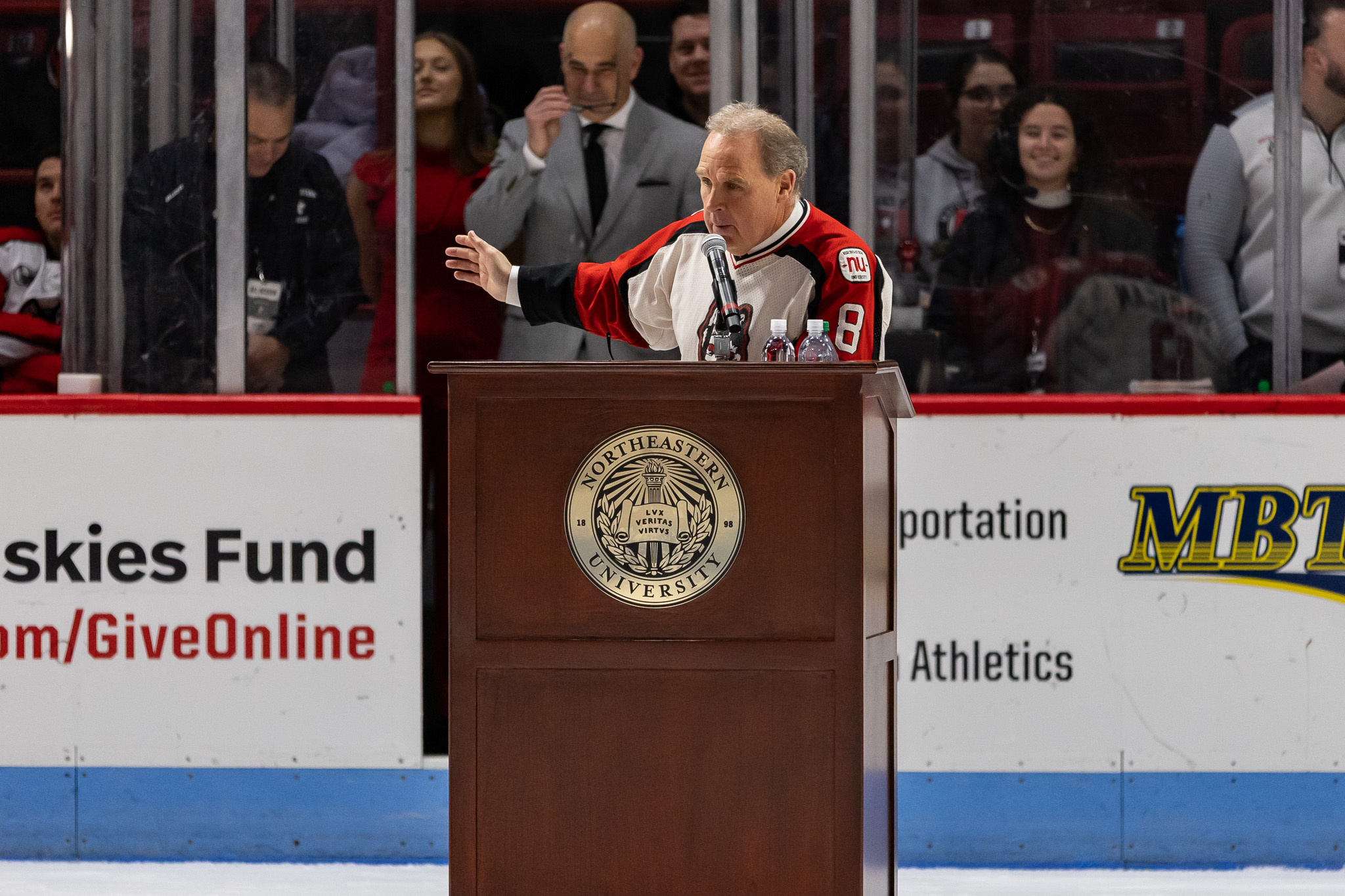

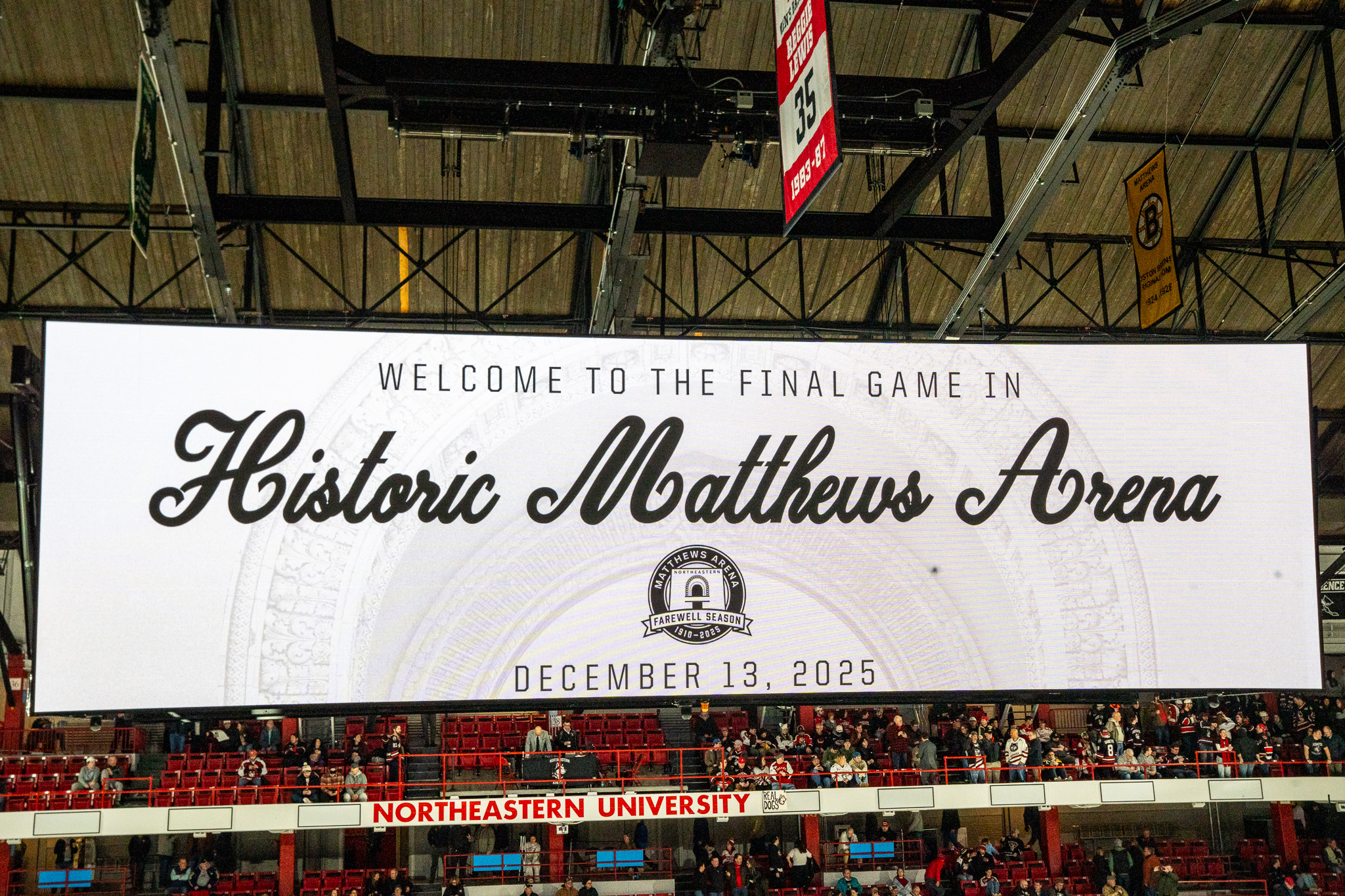

After 115 years of service to the Boston community, Matthews Arena hosted its final event Dec. 13, making way for a new state-of-the-art building.

Using the Matthews plot, Madigan and Northeastern’s plan put the final touches on a multi-score-long project to connect and develop every section of the campus. Additionally, the building will have a broader impact on all Northeastern students — not just athletics — and the city of Boston at large.

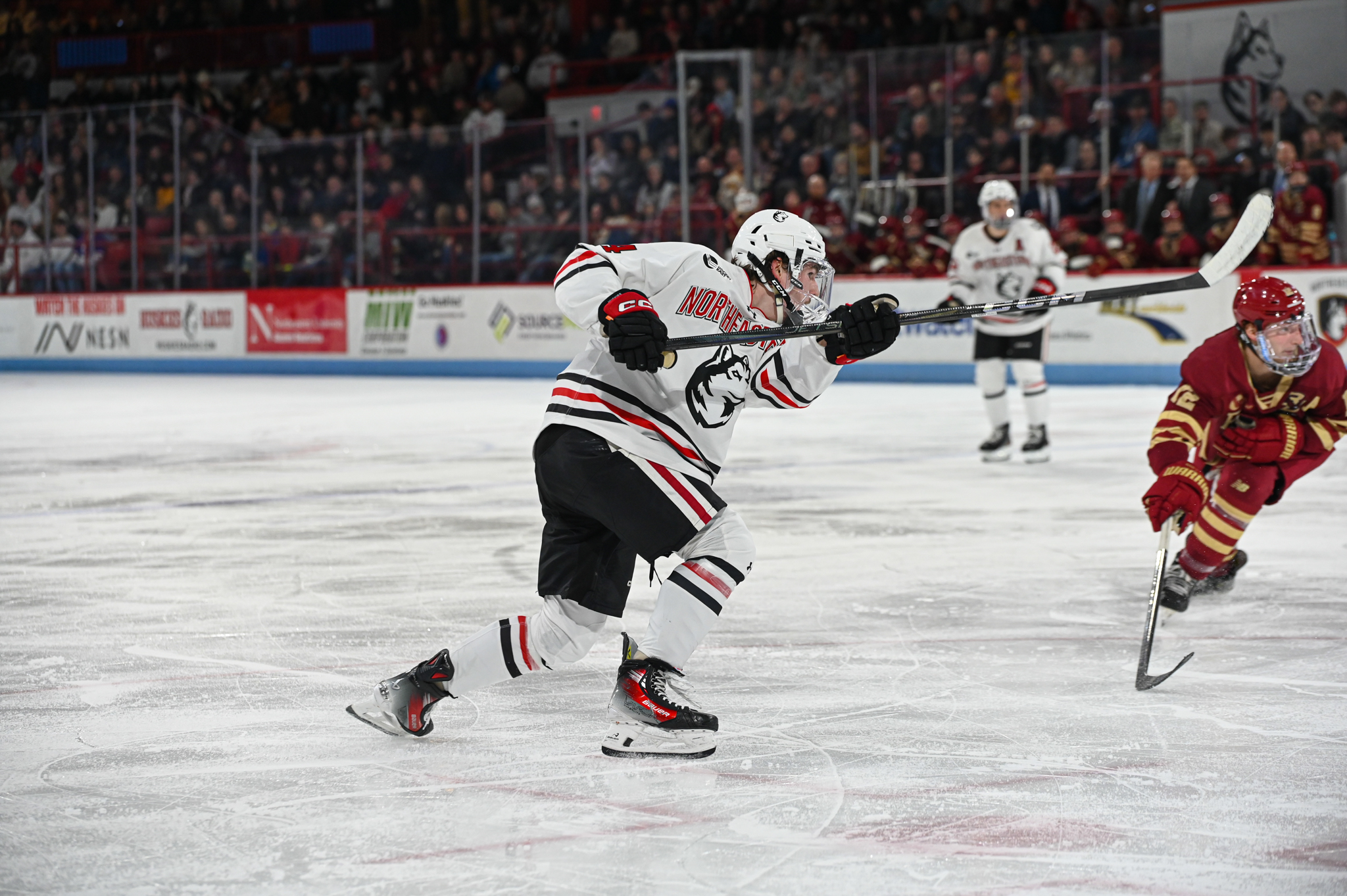

For the athletics department, of course, it is a massive enhancement. With many factors playing into recruiting and retaining players these days, top-end facilities are a must-have. For the hockey program in particular, this project will be a massive improvement and boost.

“[Matthews is] an older building, and the schools that we’re up against [when] recruiting, they’ve got all the bells and whistles,” Keefe said. “Unfortunately, that stuff does come into play, so [change is] needed, but it also shows just how much the school matters to them. That’s why we’re getting the new rink, and obviously, Coach Madigan was the driving force behind everything.”

Northeastern as an organization is particularly experienced in this type of development. In many ways, the infrastructure that the university has constructed helped position the school as a major institution.

Take 1996, when Northeastern was still largely a commuter school but with plans in the works to transition to a residential campus (i.e., the addition of the West Village). However, as it was, Northeastern was still missing key infrastructure that would create a community, so, in a sense, constructing large residential buildings would be nebulous.

To create a community — and in turn, change the university — came the Marino Physical Education Center. When that space was opened in 1996, Northeastern was no longer just a school surrounded by places to park; it was becoming a true academic institution.

“This is where I talk about ‘generational and transformational,’” Madigan said. “Marino Center helped build this campus and build a transformation: the transition from commuter-based to a residential-based campus. … That building facility was that connection to our students. [It] became a hub of student activity.”

The same phenomenon occurred years later with the development of the other side of campus. As Northeastern continued to expand, it needed to create a few expansions: high-end research facilities and more community spaces on Columbus Avenue.

Once the ISEC and EXP science centers were erected, the Columbus Ave. side of campus began to flourish. Dormitories were built, buildings were purchased, and fields were placed, all of which furthered the Northeastern community.

“You never went over to Columbus Avenue through the ‘80s and even through the mid-’90s,” Madigan recalled. “Then, we started having more of a presence over there.”

Yet, from the East Village to 60 Belvidere St., the east end of Northeastern’s campus remains largely untouched. Seemingly, it lacks the ‘community’ aspect that is present on the rest of campus. However, in Madigan’s mind, the new building will change everything by revolutionizing and connecting that part of campus and town.

“This building is going to bring it,” he declared. “It’s going to bring this area alive. It’s a [connection] to our students who are down in 60 Belvidere [and to] some of our staff members who are over in the horticultural area, and it creates this wonderful opportunity to connect back to the campus. More than anything, it creates opportunities for future development of an area.”

To put it simply, this project headed by President Aoun and Madigan will be the final step in a much larger endeavor to grow Northeastern. It also may stand as a monument representing the tremendous careers of Aoun and Madigan.

Never could 19-year-old Jim Madigan have imagined the impact he would have on the university he attended, but his 44 years of accomplishment — and navigating a few challenges along the way — have created lasting change at Northeastern.

The next two years will certainly be busy as the building is constructed, but in time, this next step in development is set to create both community and excitement as Northeastern once again expands.

“How am I feeling? I pinch myself every day. [It’s] joy, excitement, all of it kind of bundled up,” Madigan said. “Our moments and memories of [Matthews] will stay with us. … There’ll be sorrow, but [the] joy [of] knowing that what we have coming is going to serve our students, our faculty, staff, [and] student athletes for the next 100 years [is what stands out most].”

Luke Graham is the Digital Content Manager for WRBB Sports. He has covered Northeastern hockey and baseball with WRBB both on-air and in print for three years. Read all his articles here, and follow him on X here.